THE willingness of shipping lines to make direct cost outlays and forego revenue to reduce the empty container backlog shows the incredible support being given by ocean carriers to keeping Australia’s supply chain functioning.

Empty container congestion has been a problem at major ports all round the world. This is a result of unprecedented consumer demand driven by a COVID-induced shift from spending on services to spending on goods. In Sydney, the problem was exacerbated by weather events and industrial action. Carriers are being limited to their contracted container exchanges to recover schedules. For instance, if a ship has two thousand imports and is only allowed 2500 exchanges, then only 500 boxes can be exported.

Container congestion is inevitable unless additional calls are made just to pick up exports. Shipping Australia members are paying for extra ships and extra port calls in an effort to alleviate the problem.

NSW Transport and Roads Minister, Andrew Constance, has noted that record numbers of empty containers have been exported recently. He points out that in October 2020 more than 78,000 empty TEU were exported and in November more than 75,000 empty TEU were exported. That compares to a low of about 51,000 empty container exports in February and a monthly average of about 64,000 empty TEU in the preceding 12 months.

Shipping lines take action

The extra efforts by shipping lines are working. As of the time of writing this article, member shipping lines have reported they have been forced to curtail laden exports so as to evacuate empty containers. This, of course, costs a lot of money in direct costs and foregone revenues.

While one line has completely emptied its empty container stock out of NSW, others have reduced inventory significantly.

A vessel on the north-east Asia to New Zealand service has been diverted to Sydney to evacuate empties.

Two vessels will omit Melbourne and will only call at Sydney and Brisbane, and will fill up with empties.

A vessel normally deployed on the Singapore-Fremantle run will be taken out of service to run a Singapore-Sydney-Singapore voyage to load empties; that vessel has already been re-directed to pick up empties twice before.

One shipping line ran an empty loader in November to take out 1,384 empty TEU – but it had to wait seven days for a berth. That will have been at an extreme cost. Publicly available data shows that box ships were generally on charter* in late November from anywhere between US$15,500 a day for a 2,500 TEU ship up to US$36,000 a day for an 8,500 TEU ship. At the time of writing and at bottom end of that range, that’s a cost of A$143,668 to $333,683 on the charter alone before other costs (crew wages, fuel, provisions, stores, lubricants) are taken into account. This is also before the huge opportunity cost of forgone freight revenues (see more below).

To illustrate the scale of the commitment of the shipping lines, we can put some rough figures to at least one of these examples. For the avoidance of doubt or confusion, in the following illustration we have obtained figures from publicly accessible sources. The illustration below does not contain actual data from any shipping line.

Expensive: costs of deviating a ship from the Singapore-Fremantle run

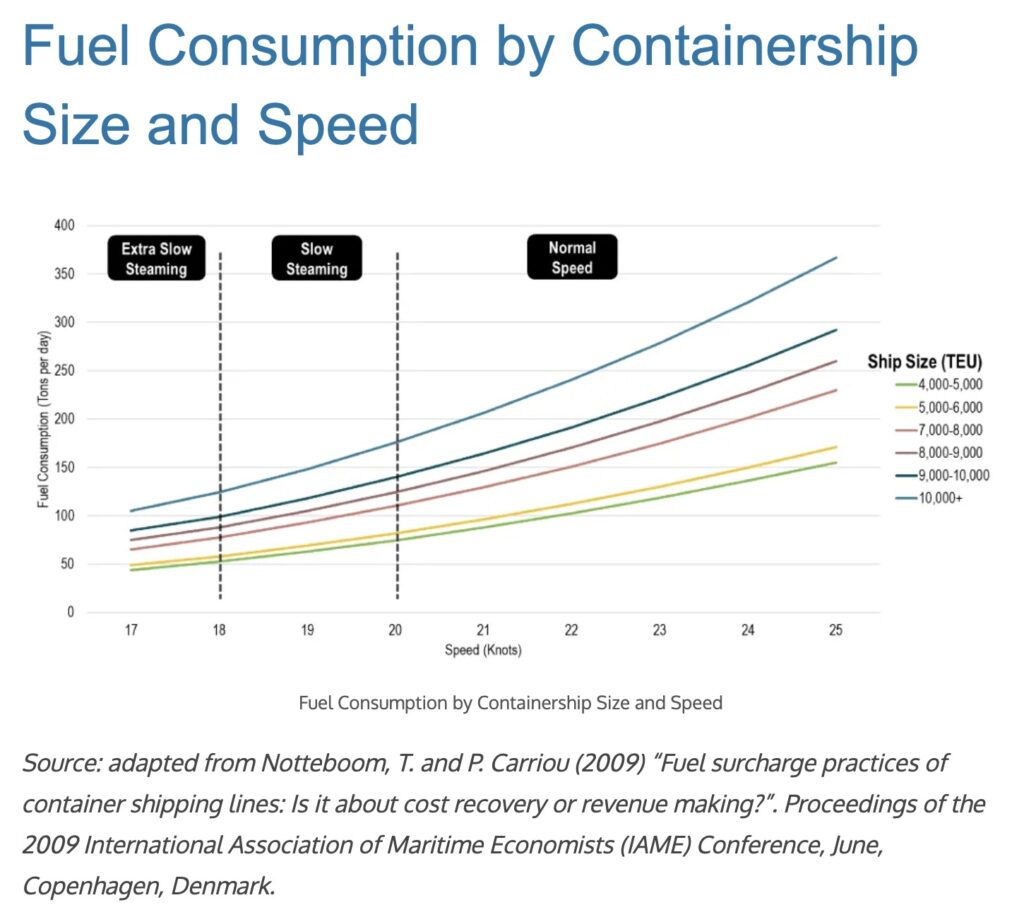

For the purpose of this illustration we will assume that the vessel deviated from the Singapore-Fremantle run is about 4,250 TEU in size. Incidentally, the non-charter direct operational costs wouldn’t be much less for a smaller ship but would be substantially greater for a bigger vessel. As ships get bigger and go faster, they consume a disproportionately greater and greater volume of fuel to overcome water resistance. A containership increasing speed from 17 to 18 knots will experience a relatively small increase in fuel consumption compared to increasing speed from 24 to 25 knots**. And, of course, the more fuel consumed, the greater the cost.

A return journey Singapore-to-Sydney is more than 9,500 plus nautical miles. At a speed of 24 knots, that’s at least a 16-day sailing time (not counting time in port). The actual sailing time may be a little more or a little less taking into account weather, currents, routing and other such variables. With crew wages, fuel, daily insurance costs, lubricants, stores, crew provisions, daily charter rate, towage, pilotage, mooring fees, port charges and so on, that’s easily a A $1.5m voyage. That voyage is completely empty with no offsetting freight revenue.

And remember: the shipping line in question has already deviated a vessel from regular service to pick up empties in Sydney at least twice.

Expensive: forgone freight revenue

Then the opportunity cost of the forgone freight has to be taken into account.

Shipping Australia understands from MizzenIT that that the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (Shanghai-to-Melbourne) can be considered as a proxy for freight rates on the Singapore-Fremantle route. The southbound freight rate Shanghai-to-Melbourne at the time of writing was about US$2,431 per TEU (A$3,229). Unfortunately, the spot freight rate simply cannot be multiplied by the number of boxes to give a rough estimate of revenues. High volume and repeat customers are likely to have negotiated discounts; some boxes will have been booked a long time ago when freight rates were much lower; different cargo may attract different freight rates according to shipping company policy and so on.

Even though a rough-figure for foregone revenues cannot be estimated, the spot-market price of the southbound freight rate does indicate that the revenues foregone are substantial.

Consider also the forgone freight rate on what would have been a return Fremantle-to-Singapore journey. According to MizzenIT, the northbound freight rate was about 62% less than southbound at the time of writing. So the estimated northbound freight rate would have been about US$924 (A$1,227) at the time of writing.

As about 57% of export boxes from Fremantle are empty, it can be further assumed that the 4,250 TEU box ship will also be 57% empty too. That would potentially give the ship about 1807 full boxes for the backhaul. Again, a lot of variables, but clearly the shipping company is forgoing a large amount of revenue on the backhaul voyage too.

There is no doubt that a shipping line deviating from the Singapore-Fremantle route to pick up boxes from Sydney is incurring massive direct financial costs and it is also foregoing a great amount of freight revenue to help clear the congestion of empty containers.

The level of demand has been unprecedented. The congestion of empty containers has been very high although it is now improving. It should be recognised by everyone that ocean carriers are doing all they can to clear the backlog and to keep international shipping containers moving through the supply chain.

This article was first published by Shipping Australia www.shippingaustralia.com.au

NOTES:

* Some ships are not actually owned by the companies that operate them and so the owners of the ships (e.g. investment funds) will charge the operators to hire them. The contract to hire a ship is called the “charterparty” and so cost of hiring the ship is called the charter rate.

** See graphic and explanation of the speed / fuel consumption phenomenon here