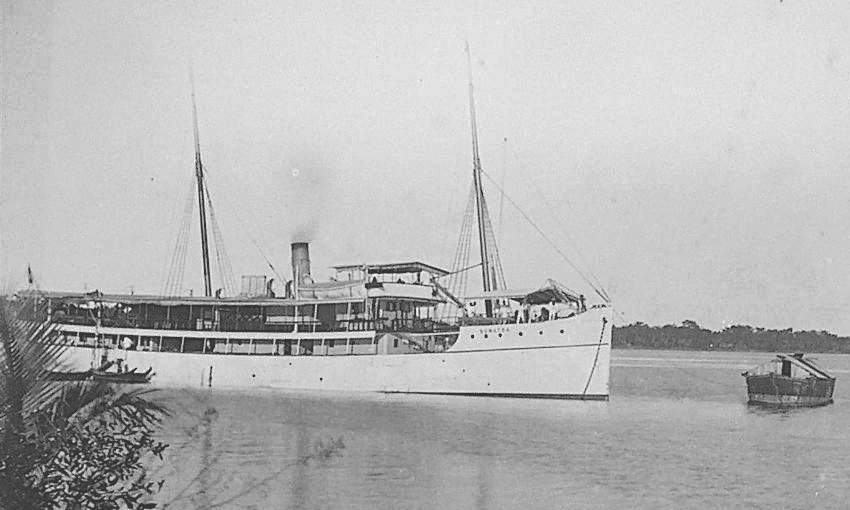

AN ISLAND steamer vanished off the coast of New South Wales one hundred years ago. The Sumatra, a Danish-built vessel belonging to the New Guinea Administration, was on its way back to Rabaul after undergoing repairs in Australia.

The Sumatra left Sydney on the afternoon of 25 June. A gale battered the east coast over the next two days, and the radio silence that followed stirred concern for the ship and the 45 people on board.

Many newspapers at the time suspected the ship had foundered, but some hope remained for the safety of the crew. But, on 2 July the Daily Commercial News reported the captain of Sumatra had washed up dead on Crescent Head Beach, shutting down the possibility of survivors and opening a royal commission.

In the meantime, the disappearance stoked months of discussion in the Australian press and shipping community about what happened in Sumatra’s final hours above the surface.

LOST WITH ALL HANDS

“The sea has given up two battered bodies proving conclusively that the island steamer Sumatra has been lost on the North Coast,” The Sun wrote in its coverage of the maritime incident.

Captain E. Bell was one of the two bodies to wash up after the storm. He was still wearing his pyjamas. The other body was that of the second officer, Sydney Fewtrell. The Sun described the face of one of the men as “considerably mutilated”, as if battered against the rocks or a wreckage.

“Fewtrell died when within reach of safety,” The Sun wrote.

“He was seen alive clinging to a plank in the surf a few minutes before he was picked up on the beach dead. There was a large cut over his left eye.

“In Sydney shipping circles it is the unanimous opinion that all hands have been lost. The tug Undaunted is patrolling for signs of wreckage.

“An official statement from the Prime Minister’s Department, Melbourne, states that the Sumatra was overhauled and passed by the navigation officer when she left Sydney. Her wireless was in good order. Her loading was correct, and the safety line was well above water.”

A Sydney radio station lost contact with Sumatra the night it disappeared. One news outlet suggested it may have gone down before the wireless operator could send out an SOS. Another suggestion was that the wireless aerial had been carried away.

Captain Richardson, master of Sumatra before its last voyage, said ships’ officers reaching port after the gale reported the weather to have been the worst they had ever experienced.

“I am afraid that the Sumatra met with the thickest of the weather and broached to when the gale was at its highest,” Captain Richardson said, as quoted in The Sun.

“The failure of the vessel to send out a wireless distress signal might have been due to damage done suddenly to the wireless operator’s quarters, which were aft. A broached-to vessel might have been swept by a tremendous sea that made the wireless apparatus useless before there was time or occasion to send out the message.

“It was a great shock to me to hear of her loss… but when I read a small paragraph in the paper last evening about a body being washed ashore on the coast, I had fears at once for the Sumatra.”

The chief engineer, second engineer, purser and wireless operator died along with the captain and second officer. The rest of the crew was from New Guinea, China and Fiji. The only passenger on board was the captain’s mother. None of them were ever seen again.

THE WRECKAGE

Pieces of Sumatra began turning up on the beach in the days and months following its disappearance.

“The wreckage picked up on the north coast, from Port Macquarie northward, establishes beyond all doubt that the Sumatra was lost,” the Sydney Morning Herald wrote.

It reported pieces of boat, timber, chairs, companion ways and part of the galley were also found. In the months that followed, vegetables, tins of tobacco, a skylight and an electric lightbulb also turned up on the beach.

The office New Guinea Trade Agency was busy after the disaster. Sydney Morning Herald said the hardest part of the chaos was communicating with families of the missing crew and answering the “anxious, heartrending” inquiries prompted by the news that the steamer was missing.

“No additional bodies have come ashore, and there has been no more evidence that would throw light on the disaster,” The Argus wrote on 3 June.

“Sensational charges have been made regarding the seaworthiness of the vessel, but these have been repudiated. It was stated today that the Commonwealth Minister would probably appoint a Royal commission to investigate the condition of the vessel, and that an inquiry is being requested by Government officials who declare that their position should be vindicated.

“There is no definite clue as to how the vessel was lost, and the disaster has aroused keen discussion in shipping circles. It is generally accepted that the vessel met her doom in the night, and the fact that only two bodies … have come ashore has led to the conclusion that the Sumatra was engulfed in huge seas, and that those below did not have a chance to escape.”

SEAWORTHINESS QUESTIONED

In the wake of the Sumatra disaster, the Sydney Morning Herald reported there had been serious allegations against the vessel’s seaworthiness, but those allegations were denied.

“The circumstances of the loss of the steamer Sumatra seem likely to remain one of the secrets of the sea,” it wrote.

“It appears that the Sumatra left Sydney without having on board an actual certificate issued by the Department of Navigation. A statement to this effect was made by the department yesterday, but it was admitted at the same time that its surveyor had passed the work done on the vessel, and there was no reason why a certificate should not have been issued, except that the vessel did not strictly come within their jurisdiction, being under the Blue Ensign.”

Then Prime Minister Stanley Bruce referred to the allegations in Federal Parliament. He said the statements made called for a thorough inquiry and investigation.

“The Sumatra, being a king’s vessel, was not subject to a Marine Inquiry, but the Government had telegraphed to the New South Wales Government, requesting that a Marine Inquiry be held,” the Prime Minister said, according to The Australian Worker, a union newspaper.

“We are waiting for this inquiry to see what is the evidence before we investigate the facts alleged against the other vessels.

“The government desires a most searching inquiry into this matter, which by reason of the deplorable loss of life has assumed the complexion of a national calamity. Every step will be taken to have it sifted to the bottom.”

INQUIRY FINDINGS

On 8 August, The Australian Worker wrote the royal commission tasked with an inquiry into the loss of Sumatra found the vessel was overwhelmed by a hurricane and that nobody was to blame. It found the vessel was seaworthy, properly loaded, and that everything was in first-class order.

“Answering the specific questions which were asked of the Commission, the Commissioners find that the Sumatra was lost at sea sometime during the night of June 26, in the vicinity of Crescent Heads and that she foundered,” The Australian Worker wrote.

“In the absence of direct evidence as to the cause of the loss, the Commissioners report that an exceptionally violent gale from the south east, approaching hurricane force, with dangerous breaking seas, overtook the Sumatra north of Tacking Point.

“If the master elected to keep the vessel running with the wind and sea a point or two abaft the beam, it was most probable that the Sumatra shipped a succession of heavy seas, which overwhelmed her, or if, as may have been, engine trouble or the low power of the vessel (maximum speed, seven knots in fine weather), it was not possible to keep the vessel heading up to the sea, and she probably fell off broadside into the trough of the sea, which overwhelmed her.”

The Australian Worker went on to denounce the inquiry and the government’s handling of affairs in the region.

“The finding of the Commission occasions no surprise. From first to last it was a ‘whitewashing’ inquiry to cover up the Federal Government’s gross mismanagement of this branch of its administration of Island affairs. The result was based on the evidence of a host of officials and departmentalists, and as such the finding was, a foregone conclusion.

“Officials of Maritime Unions at Sydney, commenting on the result, state that from the outset the Federal Government adopted a policy, of smothering all evidence, and the refusal to extend the scope of inquiry into the condition of other ships, as well as the personnel of the Commission itself, made an impartial inquiry impossible.”

This article appeared in the July 2023 edition of DCN Magazine